Like most sports, golf has a number of terms and phrases that may be unfamiliar to those who are new to the sport. “Make the cut” is one such phrase and it is an idiom that has entered into the wider vocabulary to mean “make the grade” or generally to be good enough.

Like most sports, golf has a number of terms and phrases that may be unfamiliar to those who are new to the sport. “Make the cut” is one such phrase and it is an idiom that has entered into the wider vocabulary to mean “make the grade” or generally to be good enough.

Whether you are looking to bet on golf or just simply want to watch a tournament and fully understand what is going on, our guide will give you all the info you need about the cut and how a player goes about making it.

What Is The Cut In Golf?

The cut is a method used to reduce the field size at a golf tournament and it usually takes place after two of four rounds. This will occasionally vary but the vast majority of professional golf tournaments run from Thursday to Sunday with the cut being imposed after play on Friday has finished. In other words, the cut usually takes place after 36 holes of a 72-hole event.

When Is There a Cut?

![]()

The cut is unique to golf and only occurs in stroke play events, with match play tournaments using a knockout system to reduce the field. Some tournaments have had a cut after each round, some have employed it after three rounds and others have had a cut after two rounds and then a secondary cut after the third round. However, as said, in almost all standard pro events, the cut takes place at the halfway stage of a 72-hole tournament and sees the field whittled down from around 150 players to around 80.

The number of total entrants varies from event to event but the cut regulations tend to be standardised across a tour. The cut rules govern which players “make the cut”, which means which players are allowed to continue into the weekend and which are essentially eliminated from the tournament. Only players who make the cut and thus get to complete all four rounds have a chance of winning the tournament.

Players who fail to make the cut still receive prize money but it is limited. As an example, a player who failed to make the cut at the 2021 US Masters received “just” $10,000. That compares to more than $2m for the winner, with a purse of $11.5m shared between the entire field.

The finishing position of players who failed to make the cut is listed in results as “CUT”. Of the golfers who completed all four rounds at Augusta in 2021, Australia’s Adam Scott finished last, though this was technically 54th as a host of players did not make the cut (and Matthew Wolff was disqualified). The 2013 Masters champion received almost $27,000, more than two and a half times as much as players who did not make the cut.

Why Does Golf Have The Cut?

Golf is unique in a number of ways and whilst other sports may sometimes reduce the field as an event progresses, none have a system quite like the cut. There are some who feel the cut is unfair and/or unnecessary but the main purpose of the cut is simply to remove players who are deemed not to have a chance of winning. With many tournaments having fields of well over 100 and sometimes more than 160, after two days it is often the case that a number of players are so far off the pace that they simply have no realistic chance of winning.

Critics would point to the unpredictable nature of sport and the many miracles that have occurred in golf and other sports. A player might well be last after two rounds following an opening 77 and then a 78 but who is to say they can’t shoot back-to-back 63s at the weekend to win? Stranger things have happened, undoubtedly.

However, getting rid of players who have little chance of winning is not actually an end in itself, rather it is the best way of speeding up play for the final two rounds. Most tournaments group players in threes for the opening two rounds in order to make sure all golfers can complete their rounds on schedule. The scourge of slow play has long been an issue for the sport and as players take ever longer assessing the wind, yardage, slopes and so on, things seem to be getting slower and slower.

Speeding Up The Final Two Days

The cut is, arguably, more needed than ever, as it is the only real way that we can ensure that players can play in twos on the final two days. Playing as a two-ball speeds up play dramatically and it also makes for a better spectacle as golfers go head to head. The demands of TV mean that broadcasters hold a lot of power and their scheduling needs dictate that having at least some idea of when a round will end is vital.

The cut is, arguably, more needed than ever, as it is the only real way that we can ensure that players can play in twos on the final two days. Playing as a two-ball speeds up play dramatically and it also makes for a better spectacle as golfers go head to head. The demands of TV mean that broadcasters hold a lot of power and their scheduling needs dictate that having at least some idea of when a round will end is vital.

It is also important that the players at the top of the leaderboard, who play last, are not held up by slow play in front of them. This might damage their chances and certainly it harms the tournament as a spectacle if the leaders are unable to show their best golf due to waiting around. Organisers want to avoid slow play for a range of reasons and the cut is seen as the best way to keep things moving at the most critical stage of the tournament.

In some events, the cut is used differently and in this very limited number of tournaments it is a way of reducing the tournament to a specific number of players in order to facilitate hybrid tournaments that use both stroke play and match play. The only real tournament of any note still in existence that does this is the US Amateur.

The cut here reduces the field to exactly 64, who then compete in a match play format to decide the champion. A similar system was used in the US PGA Championship for some time, whilst there have been certain other events that have worked the same way too.

What Is The Cut Rule?

The cut rule determines who makes the cut and, as said, it is generally standardised according to the tour sanctioning the event, although even then there are some exceptions. As an example, most events on the PGA Tour have a cut that includes the top 65 players and ties. That means that if 22 players are tied 65th on, for example, +2, after 36 holes, they all make the cut, meaning a field of 86 for the last two rounds. In contrast, if two players tie for 64th on scores of -4, the next player, who could be on a score of -3, is 66th and so does not make the cut.

Until relatively recently (prior to 2019) the cut rule was the top 70 and ties, with a second cut made after 54 holes in the event that 78 or more players made the initial cut. In general though, no matter what the tour, where there is a cut it is made after 36 holes and is based on the standings at that stage. Something between the top 60 and top 70 plus ties is used in the vast majority of cases.

Exceptions To The Cut Rule

There are a number of exceptions to the standard cut rules on the various tours and there are a few obvious and notable ones that merit mention. First, the events that form the FedEx Cup play-offs do not have a cut as they are already limited-field tournaments so it is not necessary. Other limited-field events also go without a cut, including, for example, the Tournament of Champions and the WGC events. It is also worth noting that the hugely popular Pebble Beach Pro-Am has a secondary cut after 54 holes, going from the top 70 after 36 holes to the top 60 after three rounds.

There are other anomalies here and there too but perhaps the most interesting thing to note about making the cut is how the majors like to make up their own rules. The Open, the Masters, the US Open and the USPGA Championship have all altered their cut rules over the years but the thing that stays the same is that they differ from the norm (currently top 65 and ties on the PGA Tour).

For example, the Masters has a relatively small field to start with, so has tended to cut the fewest players. They now allow the top 50 and ties to stay for the weekend but as the field is often fewer than 100 that is a large percentage. They used to have a 10-shot rule too, though that has been disregarded in recent years, meaning that being within 10 shots of the leader (irrespective of placing) is no longer enough to keep a player involved into “moving day”. At the time of writing none of the four majors uses the 10-shot rule, though this may of course change.

The US Open invites only the top 60 (and, as ever, ties), whilst the USPGA Championship invites the top 70 and ties to stick around, with no secondary cut even if more than 78 players make it to Saturday. The Open Championship follows the same rules, again the top 70 plus ties and again no secondary cut, though this is something that was used for a period between 1968 and 1985.

Golf Betting On The Cut

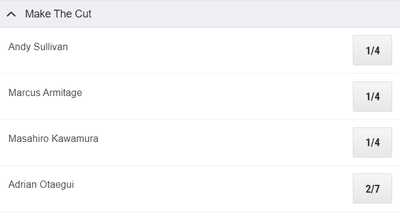

There are many different betting options when it comes to golf and some of the available markets focus on the cut. A popular pick is to back a golfer simply to make the cut. Because so many players, usually somewhere around half the field, make the cut, odds for this market are generally low. Players near the head of the outright winner market will be very short odds-on chances to make the cut, with prices of 1/9 to 1/4 fairly standard for well-fancied players. Even players who might be close to triple-digit odds to actually win the event will be priced at odds of between around 1/2 and 4/5 to make the cut, so this is not a market for punters looking to seal a big win.

There are many different betting options when it comes to golf and some of the available markets focus on the cut. A popular pick is to back a golfer simply to make the cut. Because so many players, usually somewhere around half the field, make the cut, odds for this market are generally low. Players near the head of the outright winner market will be very short odds-on chances to make the cut, with prices of 1/9 to 1/4 fairly standard for well-fancied players. Even players who might be close to triple-digit odds to actually win the event will be priced at odds of between around 1/2 and 4/5 to make the cut, so this is not a market for punters looking to seal a big win.

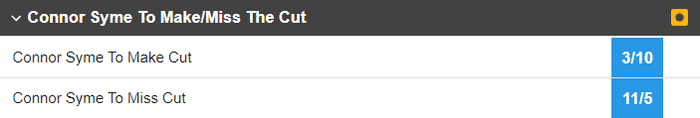

The other major market relevant to the cut is, predictably, backing a player not to make the cut. Backing a player to miss – rather than make – the cut, can offer good value when you really think a player will have an off week. A high-ranked golfer with terrible current general or course-specific form may be well priced in this market but again, given around 50% of the field will miss the cut, the odds are not all that high.

The rank outsiders will be priced at odds-on, with the players mentioned earlier, who are around the 100/1 mark to take glory, priced somewhere between evens and 6/4 to miss the cut. If you want more bang for your buck, backing a big favourite (to win the event) will return something between 3/1 and 6/1 in terms of them failing to make the cut.

Both of these cut markets can offer value for the shrewd punter. This is because the bookies tend to price them almost entirely according to the players’ odds in the outright winner market. There is certainly a strong correlation between the two but it isn’t always as direct as the odds imply. For example a top player may be very all-or-nothing, missing lots of cuts but equally securing lots of very high finishes. In this scenario there may well be occasions where they offer value to miss the cut.

On the other hand, a very steady Eddie may regularly make the cut but never challenge for victory. Their relatively low world ranking and inability to claim glory could mean their odds to make the cut are higher than they should be, again offering value to the canny golf bettor.

For the biggest events there may be further betting options when it comes to the cut. You may be able to back groups of players to make or miss the cut, or perhaps bet on the score the cut line will fall at. Bookies may also offer further specials relating to the cut – and now you understand the concept of making (or missing) the cut, hopefully you can cash in.